Back to Blogs

Discover

Bury St Edmunds and the Peasants’ Revolt

By Dr Francis Young

2021 marks the 640th anniversary of the Peasants’ Revolt, a major uprising of peasants in late medieval England. Dr Francis Young takes a look at some of the key events occurring in Bury St Edmunds.

640th Anniversary of the Peasant's Revolt

The year 2021 marks the 640th anniversary of the Peasants’ Revolt, a major uprising of peasants ‘bound to the land’ as serfs and villeins in late medieval England that marked the beginning of the end of serfdom in this country. Although the revolt was put down by the forces of King Richard II it was a major moment in England’s gradual evolution as a free society; and while the revolt ended in London, it began in East Anglia, with some of the key events occurring in Bury St Edmunds.

Historians have debated for years exactly what caused the Peasants’ Revolt, although it has traditionally been interpreted as a delayed result of the decimation of population caused by the Black Death. Landlords attempted to maintain traditional serfdom and villeinage in the face of a labour shortage and the peasantry, realising they had the leverage to demand greater freedom, eventually revolted. Whatever the truth of this explanation, the rebellion began in Sudbury on 12 June 1381 – and it was no accident that Sudbury was the home town of the unpopular Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Chancellor (at the time, effectively Prime Minister) Simon of Sudbury. A mounted group of rebels rode to Cavendish, the home of another key figure in government: Sir John Cavendish, the Chief Justice of England. The rebels raided captured and beheaded Cavendish before robbing his house and his wine cellar, and then met up with a great number of peasants who had come on foot to Long Melford.

Photo: Phil Morley

Under the command of a chaplain from Sudbury, John Wrawe, the rebels decided to march north to Bury St Edmunds, bearing the head of the Chief Justice on a pike, where they encamped outside the South Gate at nightfall on the evening of 13 June. At the time, the town was surrounded by a wall and the rebels were unsure of the loyalties of the townsfolk defending Bury, although the town had a long history of hostility to the Abbey, which was the rebels’ target. The Abbey was in a weak condition at the time; the Abbot-Elect, John Timworth, had not yet received the papal confirmation he needed to become abbot, following a bitter dispute with a rival self-proclaimed abbot, Edmund Bromefield, who aligned himself with the townsfolk and may have supported the popular Lollard heresy. In charge of the Abbey was the Prior, John Cambridge, who fled north to Mildenhall as soon as he heard the rebels were approaching. A group of rebels caught up with the unfortunate Prior on Mildenhall Heath, along with another monk named John Lakenheath, and beheaded him.

When the townsmen opened the gates to the rebels on 14 June and they entered Bury St Edmunds they carried with them the heads of Sir John Cavendish and Prior John Cambridge, and in a grisly spectacle the heads were set up in the marketplace ‘as if talking to one another’. The rebels offered to crown their leader John Wrawe ‘King of Suffolk’ but he declined the title, joking that he already had a hat. Wrawe then used his hat to crown another man, Robert Westbrom, as king. The rebels then turned their attention to their principal target: the wealthy and powerful Abbey. It was time for retribution – retribution for the ousting of Edmund Bromefield as an abbot friendly to the townsfolk, and retribution for events half a century earlier, when an earlier rebellion of the town against the Abbey was brutally put down.

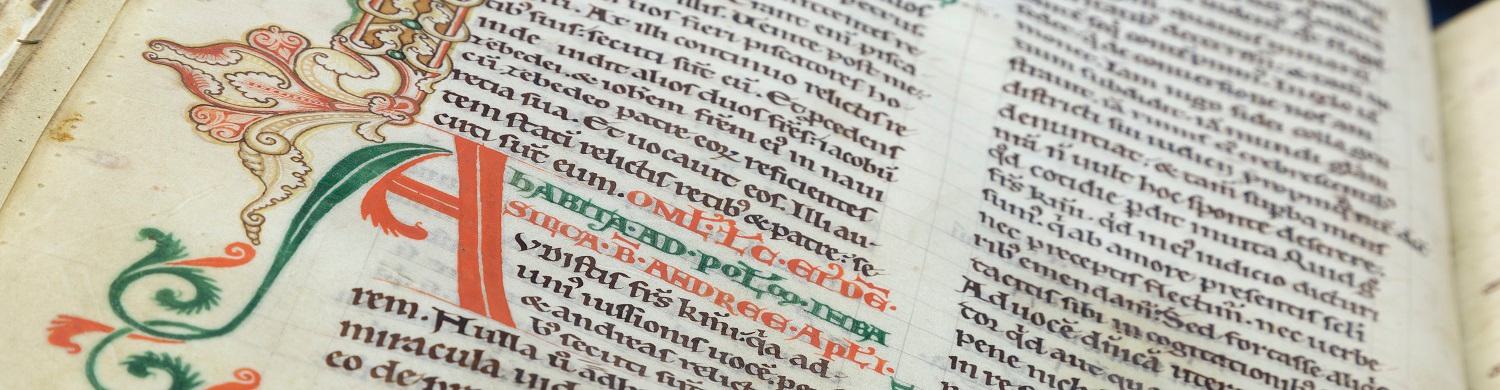

The townsfolk surged against the great Abbey Gate, built in the aftermath of that earlier rebellion and designed to defend the Abbey like a military installation; but deprived of their abbot, the monks lacked the leadership to put up any kind of fight. The rebels soon gained entry, treating the monks and beating them while they ransacked the Abbey’s offices, seizing the hated charters that formed the legal basis of the Abbey’s authority over them. The charters were taken off in triumph to the town’s Guildhall, and a charter extorted from the Abbot by rebels in 1327 was found and declared to be once more in force. Some of the monks – those who had supported Edmund Bromefield – even sided with the rebels, and took over governance of the Abbey on behalf of the townsfolk.

On 14 June, peasants from Kent were ransacking London and put Archbishop Simon of Sudbury to death; his mummified head, kept to this day in St Gregory’s Church in Sudbury, is probably Suffolk’s most famous memento of the Peasants’ Revolt. Meanwhile the Suffolk rebels’ days in control of Bury St Edmunds were numbered. Unlike in 1327, when it took months for the government to regain control, Richard II’s government was better prepared to confront the rebels. On 23 June the warlike Bishop of Norwich, Henry Despenser – a bishop better known for his crusading and military exploits than his pastoral care – led an army on Bury. The burgesses gave up the rebel leader John Wrawe, who was hanged, disembowelled, castrated and hewn into quarters. The Abbey revoked the charter of 1327 and fined the townsfolk 2000 marks for their rebellion. In 1384 Abbot Timworth was officially confirmed.

The head of Simon of Sudbury is displayed in St Gregory's Church Sudbury (photo Antony Arbuthnot)

The Peasants’ Revolt was the last major challenge to the Abbey’s authority before the Reformation, but it weakened the Abbey and it arguably never quite recovered. While the rebels had been defeated, the economic forces that had caused the revolt were not going away, and over the coming decades changing patterns of land ownership made the Abbey seem like an increasingly archaic institution, unable to adapt to economic change.

This year the Peasants’ Revolt seems a particularly timely reminder of the long-term economic effects a pandemic can have – which, for a brief period 460 years ago, plunged Bury St Edmunds into chaos.

Related Blogs

News

Abbey Gardens in Top 20 Most…

The historic Abbey Gardens in Bury St Edmunds with…

News

Abbey Project Awarded…

The project aims to conserve and protect the ruins;…

News

Cycle the Wolf Way

Winding its way around many of the best bridleways,…

News

360° Degree Vikings

The Brecks Fen Edge and Rivers Landscape Partnership…

News

Abbey Treasures

From Cambridge to Rome, we go in search of the…

Latest news

News

Where to Treat Mum: Best Afternoon Teas in Bury St Edmunds and Beyond

With Mother’s Day on the horizon, it’s the perfect opportunity to spend some quality time together. And how better to celebrate than with a delicious afternoon tea...

News

The Green Children of Woolpit

The Story of The Green Children of Woolpit - Supernatural, Folklore or Historical Mystery?

News

Rainy Day Guide to Half Term Fun

Gather the family together this February half term and discover plenty of ways to keep children entertained in and around Bury St Edmunds. From much loved picture books brought to life on stage and…

News

New in Bury St Edmunds For 2026

A sneak peak into new attractions visitors can enjoy in Bury St Edmunds in 2026.

News

Where to See Snowdrops in Bury St Edmunds and Beyond

Celebrate winter and the first signs of Spring with a walk amongst the snowdrops in Bury St Edmunds & Beyond...

News

Places to sit by a roaring fire in Bury St Edmunds & Beyond

Warm up by a roaring fire this winter in Bury St Edmunds & Beyond...

News

Tourism in Bury St Edmunds Hits Record Value, New Figures Reveal

The value of the town’s tourism economy rose in 2024 to a new record-breaking high of £55.9million.

News

Bury Tour Guides to launch new tours next year after successful 2025

Bury St Edmunds Tour Guides to Introduce new tours in 2026 and continue the successful Food and Drink Tours!

News

Baby It's Cold Outside... Things To Do When the Weather Turns Frosty

Just because the temperature’s dropped doesn’t mean the fun has to! If you’re visiting town during the chillier months, there’s still plenty to see, do, and experience.