Back to Blogs

Discover

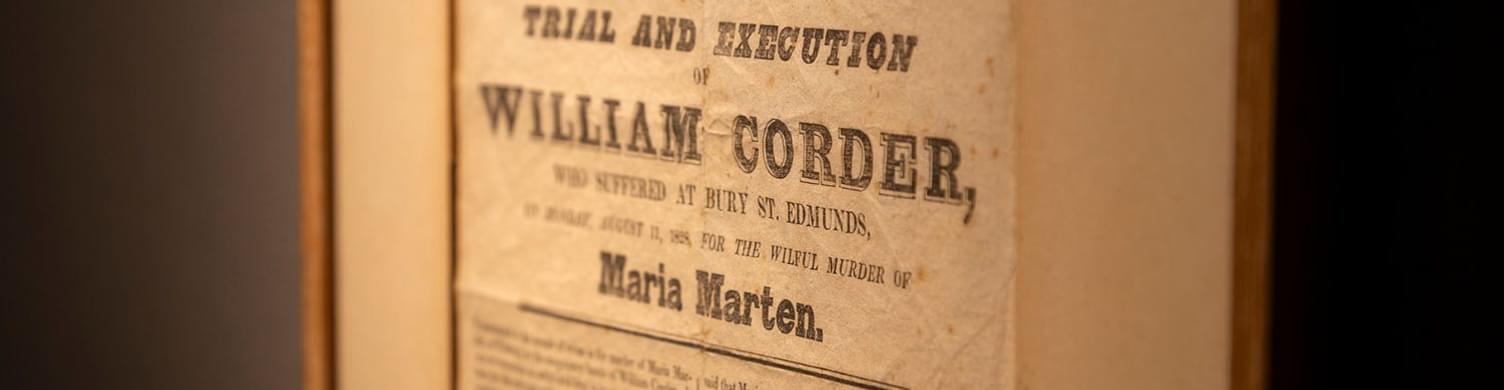

Red Barn Murder

Discover a Real life Murder Case at Moyse's Hall Museum!

West Suffolk Council Heritage Officer Alex McWhirter takes a look at the notorious Red Barn Murder and some of the artefacts from the case that are on display at Moyse's Hall Museum in Bury St Edmunds.

Murder In The Red Barn - What Happened?

The bust of William Corder and the book bound in his skin. Photo: Phil Morley

The hitherto little-known Suffolk village of Polstead was catapulted in the headlines during the years 1827-1828. This small mainly agricultural parish became infamously familiar to an increasingly literate nation of newspaper readers and gossipmongers – and remains so today.

This period marked the beginning of a true crime sensation that provokes interest and hypothesis even today, although the facts have been blurred into near obscurity with 194 years of the tale’s re-telling. It is a period that also would mark the end of several members of two Polstead families’ lives; death coming from infirmity, illness, misfortune, murder and the high Court of England.

The eponymous victim, Maria Marten was in her mid-twenties and still at this comparatively mature age, living at home with her father and stepmother, at least one sister and an illegitimate son, Thomas Henry. Her unfortunate circumstances were born of the typical plight of a labouring class girl trying to establish a household for herself away from her family’s. She had formed a relationship with the second eldest son of a middle-class family of tenant farmers, Thomas Corder. This relationship was kept clandestine under Thomas’ instructions, but the discretion could not hide a pregnancy, followed by the baby’s premature death weeks after it had been born. Any further relations would die with Thomas Corder, who not long after, accidentally drowned in the pond in Polstead. During this time Maria had sought consolation in the arms of a Peter Mayhew, a member of the landowning classes of Polstead and its environs (his sister was the landlady to whom the Corders paid rent). By him she would again fall pregnant, giving birth to Thomas Henry Marten. Under laws of Regency England recognition and remuneration was the only expectation of a father of an illegitimate child, and Mayhew duly paid five pounds quarterly to the Marten household for the child’s upkeep, an amount that annually probably rivalled that which Maria’s father Thomas contributed as a mole-catcher. The Marten family was a busy, sometimes quarrelsome household, a stepmother only ten years older than her, and a sister to also challenge any hegemony she might still have had would be motivation enough for Maria to continue seeking a conjugal relationship with another.

At this precise juncture in history the Corder family was going through its own crises. Patriarch John had died, leaving his wife and six children (4 boys and two girls) to manage their farm. As we have seen Thomas, the second eldest would die from misadventure, swiftly followed by the deaths of two of his brothers, James and John, through undisclosed poor health. Leaving Ann Corder and her daughters to keep house and home whilst the one remaining son, William inherited the burden of the family’s livelihood of a 300 acre farm, all within the space of about eighteen months.

Although clearly the couple would have already been known to one another, at what point William and Maria decided to conduct their own relationship is unclear. Equally, as to themselves would have been the knowledge of each player in this story’s ultimate and imminent doom. The remaining years of King George IV’s short reign would bring more terminal health problems to the Corder/Marten families.

William or ‘Foxy’ (this latter soubriquet to be read in the pejorative, rather than modern day understanding of the noun) and Maria conducted their own affair, also resulting in an unplanned pregnancy. Finally for Maria however, the long hoped for offer of marriage, however packed with litotes it may seem to the modern-day reader, came. The child, however, like that sired by his elder brother Thomas by Maria, was ‘sickly’ and died within weeks of birth, to be secretly buried in a field outside of Sudbury. William continued and heroically proposed a plan to Maria before her stepmother to prevent her apprehension by the parish constable for the repeat encumbrances on parish funds an illegitimate child might bear. She was to disguise herself in boys’ clothes and meet in the night at the Red Barn on Corder’s farm. There, she would change back into her own clothes and the couple would go to Ipswich to seek the necessary Banns for their wedding. This meeting would be the last Maria would have alive with anyone.

Maria Marten Found

An original article from the trial of William Corder

Both characters disappeared from the daily village goings on of Polstead shortly thereafter. Sporadic communication was made by William to Maria’s family to update them on Maria’s condition, until these too stopped. The questions would not. What was Peter Mayhew now paying an absent mother for and why should he continue? How would Thomas and Ann Marten cope with an additional mouth at the family table, but a cease to the financial contribution of £20 a year?

It was inevitable further investigation would ensue, but the proceeding events meant the investigation would be led by a constabulary. According to legend Ann Marten kept having a recurring dream disclosing the resting place of Maria, in a shallow grave within Corder’s Red Barn. This was not used as material evidence against the defendant on trial and could be the first of many concoctions to this tale.

In any case Thomas Marten went digging in the Red Barn and discovered his decomposed daughter in a shallow grave. The body was identified by the presence of a green handkerchief (Maria had this with her when last seen alive by her stepmother) and some physical abnormalities peculiar to the woman in her life; such as missing teeth and a facial cist. An inquest was carried out in the village’s Cock Inn, the forerunner to that which stands in Polstead today.

The trial of William Corder

Red Barn Murder Exhibit at Moyse's Hall Museum. Photo: Phil Morley.

Perhaps most remarkable was the investigative proceedings that traced William Corder to a girl’s school which he and his new wife Mary were running in Brentford. It is most likely his advertising for a wife in the newspaper, which would be duplicated in a national, The Times, which provided the necessary locality tip off to the arresting officers. Corder denied knowledge of a Maria Marten, but his house contained evidence suggesting he was very definitely one and the same man once associated with her. He was therefore brought back to Bury St Edmunds and its biennially held assize courts for trial for her murder.

Corder faced ten counts of murder, the number more indicative of a desire to see justice done, than the results of a scientific pathological investigation. He decided to represent himself. A mistake. And his defence maintained that she had killed herself. An insult. Not only was suicide a capital offence in itself, its offenders were condemned to a burial in unhallowed ground, and all property (such that Maria had) would have become property of the crown. William Corder wrongly read the room and was found guilty after a two day trial. He was sentenced to be hanged and then publicly anatomised in the Town’s Shire Hall.

Like all executions did, but with an additional sensationalism in this instance, thousands came to see the last moments of William Corder, hastily conducted by the state executioner John Foxton; one of his last. Many more would have come to see his anatomisation afterwards. Here one could have witnessed the colourfully unproductive attempts at ‘Galvanic Therapy’; the introduction of electricity to the dead corpse to attempt reanimation. Or simply one could have gained the visceral understanding of what a criminal’s organs look like on the outside.

Grisly End to William Corder's Remains

Photo: Keith Mindham (courtesy of Moyse's Hall Museum)

Today we are primarily left with a highly colourful and ever-changing story. The antagonist and protagonist’s houses still stand, as does the front of the prison along Sicklesmere Road before which Corder was hanged, but much of the rest of the related topography has changed or gone. George Creed, a surgeon at West Suffolk Hospital bound journalist Jay Curtis’ contemporary book of the trial in tanned skin from Corder’s body. This and other pieces of ephemera/evidence from the trial, in their varying degrees of provenance, remain on display in Bury St Edmunds’ museum Moyse’s Hall.

Much has been made of the rest of William Corder’s remains. The skull was retained for its phrenological value. At some point the head and skeletal body were apparently repatriated and for many years were used as an anatomical aid at West Suffolk hospital. Eventually these were housed in the Royal College of Surgeons Museum in London until they were cremated in 2004. Realistically, these bones were certainly in a highly degraded state. In their years of anatomical instruction they had been kept in a bag emptied before each year’s influx of medical students. This degradation was such that in the 1940s patella bones had to be replaced with wooden carved ones when an attempt was made to rebuild the complete skeleton. There is also no evidence to suggest that the highly prized phrenological sample that was William’s skull was ever reunited with his body.

Today’s modern tourist can make the same journey that our macabre minded tourist ancestors did and see some of the principle buildings in the story. A wooden plaque on the wall of St Mary’s Polstead is all that remains in place of the souvenir hunted gravestone to Maria. with a death mask, pistols, bust and the skin bound book of William Corder’s trial, alongside some less well provenanced but associated ephemera, the staff at Moyse’s Hall Museum, are happy to fill in the blanks to this Horrible History when visited.

The ear of William Corder. Another grisly item in the Terrible Tales exhibit. Photo: Phil Morley

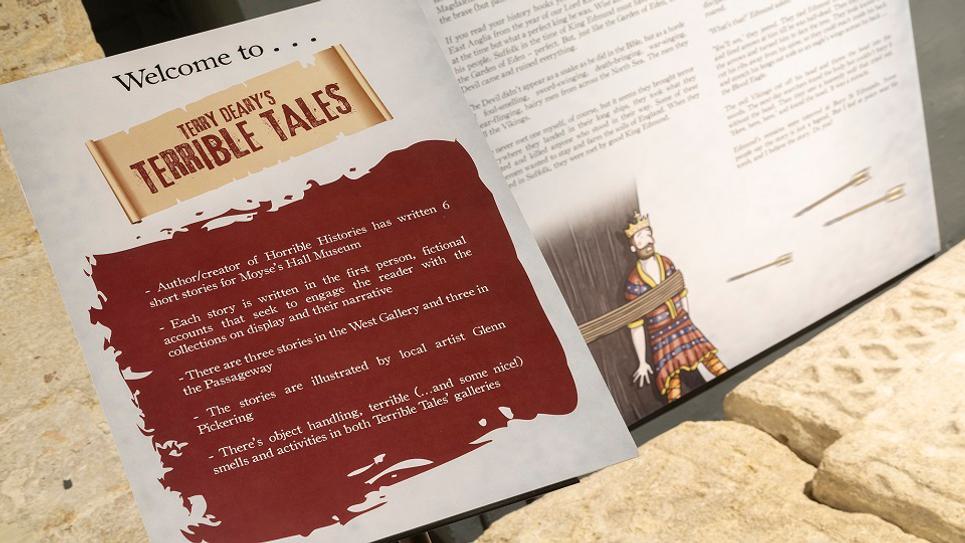

Horrible History Creator's Terrible Tales at Moyse's Hall Museum

Horrible Histories creator Terry Deary has helped Moyse’s Hall Museum bring Bury St Edmunds’ gruesome history to life for children.

Moyse’s Hall Museum not only features six Terrible Tales by Terry Deary, best-selling author and creator of the hugely popular Horrible Histories books, but also some grisly and gruesome interactive displays for children and adults.

Step inside a gibbet cage (made for the museum by blacksmiths Kingdom Forge), try on a ball and chain for size, experience the smells of history including the wretched tanner’s pits, handle thumbscrews and try on manacles, pick up a Norman sword and experience the disease box where visitors can smell a pus ridden hand - a museum favourite!

Find out more about Moyse's Hall Museum at their website.

Related Blogs

News

The Green Children of Woolpit

The Story of The Green Children of Woolpit -…

News

Bury Tour Guides to launch…

Bury St Edmunds Tour Guides to Introduce new tours in…

News

Town’s Museum Forms New…

Moyse’s Hall Museum will be forging links with a…

News

St Edmundsbury Cathedral…

St Edmundsbury Cathedral in Bury St Edmunds is…

News

Bury St Edmunds & Beyond…

Step inside many of Bury St Edmunds historic buildings…

Latest news

News

Where to Treat Mum: Best Afternoon Teas in Bury St Edmunds and Beyond

With Mother’s Day on the horizon, it’s the perfect opportunity to spend some quality time together. And how better to celebrate than with a delicious afternoon tea...

News

The Green Children of Woolpit

The Story of The Green Children of Woolpit - Supernatural, Folklore or Historical Mystery?

News

Rainy Day Guide to Half Term Fun

Gather the family together this February half term and discover plenty of ways to keep children entertained in and around Bury St Edmunds. From much loved picture books brought to life on stage and…

News

New in Bury St Edmunds For 2026

A sneak peak into new attractions visitors can enjoy in Bury St Edmunds in 2026.

News

Where to See Snowdrops in Bury St Edmunds and Beyond

Celebrate winter and the first signs of Spring with a walk amongst the snowdrops in Bury St Edmunds & Beyond...

News

Places to sit by a roaring fire in Bury St Edmunds & Beyond

Warm up by a roaring fire this winter in Bury St Edmunds & Beyond...

News

Tourism in Bury St Edmunds Hits Record Value, New Figures Reveal

The value of the town’s tourism economy rose in 2024 to a new record-breaking high of £55.9million.

News

Bury Tour Guides to launch new tours next year after successful 2025

Bury St Edmunds Tour Guides to Introduce new tours in 2026 and continue the successful Food and Drink Tours!

News

Baby It's Cold Outside... Things To Do When the Weather Turns Frosty

Just because the temperature’s dropped doesn’t mean the fun has to! If you’re visiting town during the chillier months, there’s still plenty to see, do, and experience.