Back to Blogs

Discover

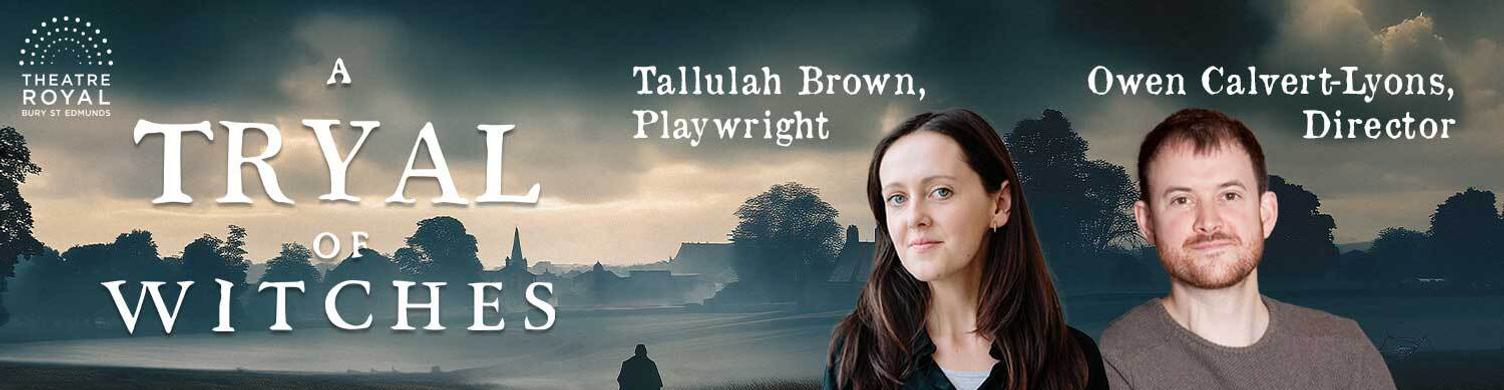

The Bury St Edmunds Witch Trials are the Focus of a New Production by Theatre Royal Bury St Edmunds

A Tryal of Witches

We speak to writer Tallulah Brown and Director Owen Calvert Lyons about their new production, 'A Tryal of Witches' and how the play's themes are still very much as relevant today as they were in the 1600s.

The play asks what led to one of the most shocking witch trials in British history.

Q: A Tryal of Witches is based on the largest witch trial in England’s history and another which influenced the Salem Witch Trials, both of which happened here in Bury St Edmunds. How did you go about researching the history of the trials and what surprised you?

Tallulah: Both trials I researched (one in 1645 and one in 1662) had elements that were deeply shocking. I spent days in the Suffolk archives sifting through pages of research and honed in on pamphlets printed at the time of the trials detailing what happened. I was shocked by the silence of the women, their lack of voice, their lack of defence. The lack of information we have about these women allowed me to embark on my story. I set out to give them voices.

I had read Malcolm Gaskill's book on Witchfinders which is extremely detailed and disturbing but it wasn’t until I read the Manningtree Witches by AK Blakemore that I started thinking about how I could blend fact and fiction, poetry and music. In the first trial 18 women were hanged on one day. The night before the trial there were reports of them singing together in a barn outside Bury St Edmunds.

My play is set in 1645 - despite drawing on both trials - the civil war had reached a really interesting moment, especially for East Anglia. Just months before the New Model Army won the Battle of Naseby. Cromwell had successfully recruited men from the villages of Suffolk. Then Hopkins arrived with his persuasive rhetoric - he told everyone who would listen that he knew the reason for all the unrest. So you have the war, an absence of men in the villages, a hot Summer and another failed harvest - a tinderbox.

Q: What drew you to the subject?

Tallulah: I grew up in Aldeburgh and always knew that seven women were kept in the Moot Hall for weeks and weeks before being hanged. You can still see the ‘witch marks’ etched above one of the office doors. As a child I saw this is as spooky but as I got older the enormity of it grew - the gross injustice, the horror, the violence.

Even though the subject is historical I feel the themes are sadly and painfully modern. Puritanical language still seeps into debates over women’s rights - whether that’s in regards to sexual assault, abortion or rape. The judge who sat in on the trial in 1662 and found both women guilty of being witches was called Sir Matthew Hale. He was recently quoted by Justice Alito in striking down Roe vs Wade. Even though this is an exploration into the past, it’s scarily prescient.

Arthur Miller’s The Crucible is one of my favourite plays but the character of Abigail is older, more ‘wiley.’ In the Suffolk trial the children brought in to testify were really young. The more I researched the more I felt that writing this play from a female perspective, writing a story that put the women accused centre stage was important. They are women just like us - their fears, their dreams, their hopes and desires just like ours.

Q: Did you manage to find out why many of the people who were hanged were accused of witchcraft?

Tallulah: Margaret Atwood makes this interesting point regarding the Salem Witch Trials (that were linked) which was that every accusation was rooted in a real event. That is to say there would be a birth, or a death, an illness, a stroke - something that was beyond the shadow of doubt. And then from this came the human need to blame someone for things that are often out of our control. My play starts with the birth of a baby - and from that birth come the accusations. In 1645 there were accounts of bewitched beer, a comet crossed the sky - that Summer was too hot, the Winter too cold, the crops failed, illness prevailed. Seen through a lens of blame and panic even the death of an animal could mean the devil’s work. Hopkins saw women as sexual predators, there to seduce men.

For me the saddest reports I read came from women unable to get pregnant. Gaskill makes the point that fertility was a commodity - often the only commodity women had. They would consult herbalists or midwives - which in turn made them the perfect targets for Hopkins. My character of Anne is a wise woman, a midwife, a healer. The villagers have previously gone to her for help and then are too scared to defend her when she’s accused.

Q: This trial was the first time women were convicted using spectral evidence - the belief that witches could be in two places at one time. How did you think this extraordinary claim came about and what impact did it have?

Tallulah: Sir Matthew Hale was hugely respected and for him to have sat in on this trial is monumental. Where Hopkins can be seen as a demented fantasist, Hale was a renowned scholar, barrister and judge, someone who is still quoted today. The claim of ‘spectral evidence’ came about because of an argument - that truly did begin over a fish - an old woman falls out with a merchant over begging for food (the Poor Relief Act in 1601 decreed the poor should be cared for by almshouses and so people’s attitude to begging really changed.) An argument blows up between the old woman begging and the wealthy merchant and it’s his children that then start having these visions. Spectral evidence meant that women couldn’t have alibis - if you could prove you were elsewhere that meant nothing because if you were a witch the devil could take your image. It meant women had no way to defend themselves.

Q: Many people would be surprised to learn that the witch trials in Salem in Massachusetts came after England’s witch trials. How do you think the trials here impacted what happened in the US?

Tallulah: We now know that there was direct impact. Sir Matthew Hales description of the trial ‘A Tryal of Witches’ was published and travelled across to Salem. New England looked towards the puritans back in England for advice and guidance particularly when things were going wrong - and by that I mean failed harvests, bad weather, these were all considered signs that God was displeased.

Q: Tallulah, you are in the band TRILLS, (winners of a Music and Sound Award for Best Original Composition for their song on the Suffragette film trailer) which has provided the music for the play. How did you go about scoring the play?

Tallulah: When I read about the women singing the night before their trial it was such an evocative image. There are four of us in the band - we’ve been singing together since we were teenagers. We write by adding harmonies, repeating a line over and over until the harmony is right, all by ear. At the time, the captured women sang a psalm but I wanted the songs in the play to feel elemental, guttural, almost pagan. I wanted the songs to feel like something was being summoned from spirits, from old gods, from the earth. In Greek Myth the furies were goddess of revenge - in the script the songs are sung by ‘the furies’, as opposed to specific characters in the play. The songs are being sung by women who have walked this Earth before, who are here to tell their story.

When it came to the lyrics we looked at the poetry Hildegard of Bingen, the medieval abbess who celebrated the sacred in nature. I was also reading a lot of William Blake at the time - his Songs of Innocence and Experience. Ultimately the music turns the horror into something beautiful. It gives the play its hope, the transcendence, the promise of a better future. The telling of the story isn’t the righting of wrongs but an acknowledgement.

Q: Owen, many people who remember reading The Crucible when they were at school were impacted by just how friends and neighbours could turn on one another. Did this play inspire your production?

Owen: The events depicted in The Crucible have a direct connection to our story. The witch trials in Bury St Edmunds were written up and published at the time. These accounts were then used during the witch trials in Salem, Massachusetts as proof of the ‘legitimacy’ of such trials. So the events which took place in our town had far reaching consequences around the world.

Q: As the play is set in Bury St Edmunds, is it a story for people living in our town or do you think it will have wider appeal?

Owen: Whilst our play very much focuses on the events which took place in Bury St Edmunds, I think the English witch trials hold a fascination for lots of people in this country. We saw with our last production, Richard, My Richard that audiences will travel a long way to see great theatre about subjects which interest them. We are fortunate that Theatre Royal is located in such a beautiful town, so I have no doubt that A Tryal of Witches will attract tourists and residents alike.

Q: The play’s run coincides with International Women’s Day and we know these were trials of mainly women. Was the timing deliberate?

Owen: Yes, International Women’s Day is an important date in our calendar. Over the past few years we have staged great plays by women in the Spring slot: Home, I’m Darling by Laura Wade and The Children by Lucy Kirkwood, both of which had great female leads. This play came about through discussions within the Theatre Royal team about the Sarah Everard case and the rise in violence against women. If feels right that we will be presenting the play on such an auspicious date.

Q: Given that it seems we are in a time when finger pointing, name calling is rife on social media right now. What do you hope people will take away from seeing the play?

Owen: One element of the play (and the history it is based on) that continues to shock me is how willing people were to listen and give credence to Matthew Hopkins (the self-proclaimed Witch Finder General), even though what he was saying was really wild. I think this feels very resonant right now. We are again in a moment in time in which people are willing to follow powerful and charismatic leaders, regardless of the costs. I hope that people will take great strength away from seeing this production. I don’t think I’m giving anything away by saying that these characters were killed – those are the historical facts – but there is something enormously empowering about witnessing stories of injustice. They can light a fire in your belly. That’s what I’m hoping for.

The play asks what led to one of the most shocking witch trials in British history.

East Anglia, 1645, a hot and stifling Summer. The air is thick with paranoia and superstition.

Matthew Hopkins, the self-appointed Witchfinder General travels from village to village telling all who will listen about the power of the devil and the prevalence of witches.

As the bloody battles of the civil war draw ever closer, the crops fail and a man drops dead in the alehouse.

A moral panic sets in, they need someone to blame.

Far from being a trial of witches, this was a trial of women.

The play asks what led to one of the most shocking witch trials in British history. The trial in Bury St Edmunds was the first time women were convicted using spectral evidence - the belief that witches could be in two places at one time.

A new play with original music composed by the band, TRILLS.

Written by Tallulah Brown.

Directed by Owen Calvert-Lyons, Director of Theatre Royal Bury St Edmunds.

Friday 7th - Saturday 22nd March

Tickets £12-£30.

Book your tickets now at Theatre Royal Bury St Edmunds website.

Watch the play's trailer now!

Superstition: Strange Wonders & Curiosities

This Spring, the Superstition: Strange Wonders and Curiosities Exhibition at Moyse's Hall Museum will explore folklore, witchcraft, and beliefs from within our own collection, supported with artefacts from other institutions and private individuals.

The ghostly Black Shuck of East Anglia, 17th Century ritualistic artifacts, new ‘witchcraft’ acquisitions and donations, 19th Century oddities, ancient relics, and much more, will help tell the story of superstition throughout the ages.

The exhibition has been inspired by the ‘A Tryal of Witches’ production at the Theatre Royal Bury St Edmunds and features a number of talks.

Book tickets to the exhibition at Moyse's Hall Museum website. Tickets are priced at Adults £5, Senior Citizens £4.50, Child 5-16 and full-time students £3. Under 5s Free.

Tickets are for entry to the museum, which includes the exhibition, so you can explore all of the exhibition areas. Steeped in history, Moyse's Hall has looked out over Bury St Edmunds market place for almost 900 years. The landmark 12th century building rich and varied past has included serving as the town Bridewell, workhouse and police station, first opening as a museum in 1899.

Today the museum offers a fascinating view into the past with collections that document the foundation of the early town including the creation and dissolution of the Abbey of St Edmund; Crime and Punishment, which includes six Terrible Tales by Terry Deary, best-selling author and creator of the hugely popular Horrible Histories books, and some grisly and gruesome interactive displays for children and adults. Plus remarkable collections relating to the notorious Red Barn Murder, a world class collection of exquisite collections of clocks and timepieces including rare items bequeathed by musician and clock collector Frederic Greshom-Parkington and fine art by Sir Peter Lely, Angelica Kauffman, James Tissot, and England's first professional female painter Mary Beale.

Find out more about hauntings, witches, and more in our Spooky Bury St Edmunds Guide.

Related Blogs

News

How to Spend Betwixtmas in…

The post Christmas period is the perfect time to get…

News

New in Bury St Edmunds For…

A sneak peak into new attractions visitors can enjoy…

News

Festive Theatre Guide 2025

There’s no better way to summon the magic of the…

News

Bury St Edmunds Comedy…

The 2026 line-up includes Seann Walsh, Luke Wright,…

News

Keaton’s Batman the star in…

The iconic cowl created for Michael Keaton in Tim…

Latest news

News

Tourism in Bury St Edmunds Hits Record Value, New Figures Reveal

The value of the town’s tourism economy rose in 2024 to a new record-breaking high of £55.9million.

News

How to Spend Betwixtmas in Bury St Edmunds & Beyond

The post Christmas period is the perfect time to get out and about before the new year kicks in, and you’ll find plenty of activities and places to visit in Bury St Edmunds and beyond.

News

Parents Guide to Pre Christmas Entertainment

It's the school holidays and with Christmas just around the corner we've put toegther a guide on places to take the kids to keep them entertained until Santa visits!

News

Enjoy a Festive Afternoon Tea in 2025

Celebrate the Christmas season with a festive afternoon tea in Bury St Edmunds & Beyond...

News

Festive Winter Walks

Get outside and enjoy the fresh crisp winter air with one of these walks in Bury St Edmunds and Beyond!

News

Bury Tour Guides to launch new tours next year after successful 2025

Bury St Edmunds Tour Guides to Introduce new tours in 2026 and continue the successful Food and Drink Tours!

News

New in Bury St Edmunds For 2026

A sneak peak into new attractions visitors can enjoy in Bury St Edmunds in 2026.

News

Baby It's Cold Outside... Things To Do When the Weather Turns Frosty

Just because the temperature’s dropped doesn’t mean the fun has to! If you’re visiting town during the chillier months, there’s still plenty to see, do, and experience.

News

Places to sit by a roaring fire in Bury St Edmunds & Beyond

Warm up by a roaring fire this winter in Bury St Edmunds & Beyond...